Creating Anki cards for Russian Coursera MOOC with stemming and frequency lists

April 16, 2014, [MD]

In which I automatically generate Anki review cards for vocabulary based on subtitles from a Russian Coursera MOOC

Learning Russian, a 10-year project

I have been working on my Russian on and off for many years, I'm at the level where I don't feel the need for textbooks, but my understanding is not quite good enough for authentic media yet. I've experimented with readings novels in parallel (English and Russian side by side, or Swedish and Russian, like on the picture), and I've been listening to a great podcast for Russian learners.

Language learning with MOOCs

MOOCs can be a great resource for language learning, whether intentionally or not. At the University of Toronto, we found that more than 60% of learners across all MOOCs spoke English as a second language, no doubt some of them are not just viewing the foreign language of the MOOC as a barrier, but are also hoping to improve their English. To my delight, the availability of non-English language MOOCs has been growing steadily. For example, Coursera has courses in Chinese, French, Spanish, Russian, Turkish, German, Hebrew and Arabic. There are also MOOC providers focused on specific linguistic areas, for example China's XueTangX, France's Université Numérique, and Germany's iversity.

MOOCs can be a great resource for language learning, whether intentionally or not. At the University of Toronto, we found that more than 60% of learners across all MOOCs spoke English as a second language, no doubt some of them are not just viewing the foreign language of the MOOC as a barrier, but are also hoping to improve their English. To my delight, the availability of non-English language MOOCs has been growing steadily. For example, Coursera has courses in Chinese, French, Spanish, Russian, Turkish, German, Hebrew and Arabic. There are also MOOC providers focused on specific linguistic areas, for example China's XueTangX, France's Université Numérique, and Germany's iversity.

The existence of global open educational resources is nothing new. Five years ago, I wanted to share my enthusiasm about being able to "peek through the windows" of universities around the world, and edited a YouTube mashup. I've also blogged about OER for a multicultural classroom, and written about OER from China, India, Indonesia, etc.

However, earlier OER videos tended to be full lecture recordings, with poor video and audio quality, often on proprietary and hard to use platforms, with very little facilitation for online learning. Current MOOC platforms have converged around short (5-15 minutes) videos, with high video and audio quality, and decent video players. The courses are coherent, designed for online learning, and often feature supporting readings, sometimes even subtitles, etc.

A Russian MOOC

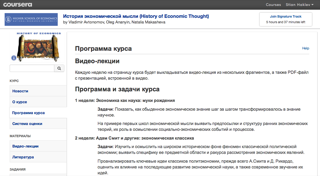

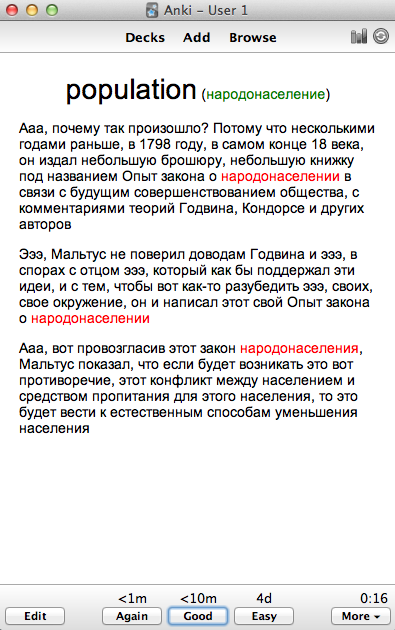

The picture above is from a lecture in the MOOC "История экономической мысли" (History of Economic Thought), which is currently in it's second week on Coursera. I signed up for this several months ago, because I wanted to try out my Russian, and I find the topic very interesting. (Extra interesting, of course, is the question of whether this topic will be taught any differently from a country that has a very unique history with regard to economic thought and experiments). The fact that I know something about the topic, and about European history in general, makes it easier to follow the lectures, as do the subtitles, the ability to regulate the speed, and the occasional illustrations in the video. Watching a few of the videos, I found that I could more or less follow along, but there were a number of words that seemed important, and which I could not understand.

Stemming and word frequencies

I've always been interested in language technology, and last year I spent some time experimenting with different libraries to create word frequency lists from Russian electronic texts. I used a library to "stem words" -- reducing all the conjugated forms of a word to a single word -- for example all these forms of the word big: большая, больше, большей, большие, большим, большими, большое, большой, большую. There are several possible libraries for doing this, none are perfect, but most are quite good. In my previous blog post, I used the Ruby gem ruby-stemmer, however when I revisited my code, I noticed that I had switched to using hunspell after writing the blog post.

Hunspell is an open-source spellchecker, which is also able to output word stems. In the example below, I simply send a Russian sentence through hunspell, and get back a list with the original conjugated word on the left, and the stem on the right (I've removed the words that didn't change)

❯❯❯ echo "Сегодня наше предствавление об экономике очень сильно отличается от того,

как люди древности эээ, мыслили то, что мы сегодня называем экономикой." |

hunspell -d ru_RU,ru_RU_google -s

экономике экономика

сильно сильный

отличается отличаться

древности древность

мыслили мыслить

называем называть

экономикой экономика

Getting word frequencies from a MOOC subtitle file

Not only did I have this old project with stemming and creating frequency lists of Russian words, but I have recently done some experiments with downloading video subtitles from Coursera courses for use in a machine learning project. This script takes an HTML file with the list of course lectures (you need to be logged in to get to this page, so the easiest is to open it in the browser, and save the page), extracts all the subtitle links, downloads them, and concatenates them to one output file.

Not only did I have this old project with stemming and creating frequency lists of Russian words, but I have recently done some experiments with downloading video subtitles from Coursera courses for use in a machine learning project. This script takes an HTML file with the list of course lectures (you need to be logged in to get to this page, so the easiest is to open it in the browser, and save the page), extracts all the subtitle links, downloads them, and concatenates them to one output file.

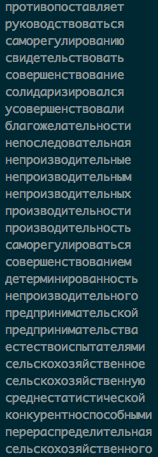

We can then pass this file through the stemmer (all code for this blogpost on Github), and generate a list of all word-stems that occur more than five times, sorted by general frequency. (I use a Russian frequency word list I found here). The subtitles for the first two weeks of videos (18 videos) total 27,600 words (50-80 pages of printed text). There are almost 6,400 unique words (of which сельскохозяйственного -- agricultural -- is the longest), but only 3374 stems. By removing all stems that occur less than five times, we're down to a much more manageable 839 stems.

I opened these in a text editor, and manually removed words I already knew (I left in many words which I kind of knew, but would like to learn more precisely). Since the words were sorted in order of global frequency, with more "rare" words near the top, I could remove most of the lower half of the file in one swoop (words like "I", "like", "and", etc). Within half an hour, I had now gone from 27,600 words to 184 word stems that I needed to learn or study.

I opened these in a text editor, and manually removed words I already knew (I left in many words which I kind of knew, but would like to learn more precisely). Since the words were sorted in order of global frequency, with more "rare" words near the top, I could remove most of the lower half of the file in one swoop (words like "I", "like", "and", etc). Within half an hour, I had now gone from 27,600 words to 184 word stems that I needed to learn or study.

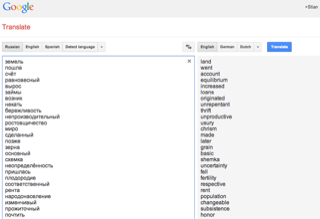

No problem, just copy the whole list of Russian words into Google Translate, and out comes an equally long list of English corresponding words, which I save to another text file. (These are not 100% perfect, but in my experience, it works for 95% of the words).

Bringing it all together - Anki and spaced repetition

A common concept on language learning blogs is "spaced repetition", the concept of having a computer automatically determine the optimal repetition rate to counteract the natural rate of forgetting. Anki is a great free program for practicing flashcards using spaced repetition, with very powerful options to create your own cards, configuring the rate of repetition, etc. I have only ever used it before with public decks, but I thought I would try to use the tools I introduced above to make my own cards.

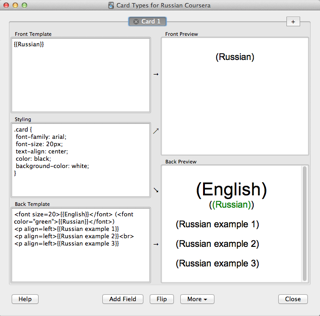

The simplest cards can be represented as two columns in a file, the front and the back. You are presented with the word on the front, try to remember the word on the back, turn the card, and indicate whether you were successful or not. However, Anki supports much more powerful card configurations. You create a new note type, with arbitrary many fields, and then you can create different card designs, incorporating these designs.

The simplest cards can be represented as two columns in a file, the front and the back. You are presented with the word on the front, try to remember the word on the back, turn the card, and indicate whether you were successful or not. However, Anki supports much more powerful card configurations. You create a new note type, with arbitrary many fields, and then you can create different card designs, incorporating these designs.

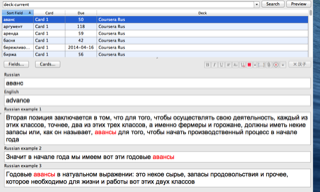

I decided that it would be very helpful to see the words in context as well. And not just in an arbitrary context, but in the specific context from the course. Given that I had already gone from specific words to the word stem, I could go back to using those specific words to search for example sentences, add highlighting of the word in question, and include these in the file. Each card has a Russian word on the front, and when you turn it, you see the English translation (from Google Translate), the Russian stem (for reference), and up to three example sentences with the word highlighted.

I think the result is pretty awesome. It will be fun to practice on these cards, and then go back to watching the videos. When next week's videos are released, I should be able to quickly generate a list of words that are new (were not covered in week 1 or 2).

I think the result is pretty awesome. It will be fun to practice on these cards, and then go back to watching the videos. When next week's videos are released, I should be able to quickly generate a list of words that are new (were not covered in week 1 or 2).

There are of course many ways in which this could be improved. I'm thinking of how to keep track of words I know, so that I can easily remove them when getting a word list from new material. Integrating this kind of functionality into the Coursera or other MOOC platforms would be neat, although it will probably never happen. (If they had more open APIs, other people could build it, however). I could for example easily extract the timing of the example sentences, and include that in the flash cards, so you could jump straight to a specific video at the point where the professor says a certain example sentence (however, I don't know how to generate URLs that open a Coursera video at a specific time).

There's also a lot of other fun stuff one could do with subtitles - it would be great if we could get easy access to subtitles for all the courses, and use it to build a search engine (linked directly to videos etc.)

But for now, I need to study some flashcards, and watch some Russian videos. Пока!

(All the code on Github)

Stian Håklev April 16, 2014 Toronto, Canada comments powered by Disqus