Supporting idea convergence through pedagogical scripts and Etherpad APIs, an introduction

October 3, 2014, [MD]

We can script Etherpad to push discussion prompts out to many small groups, and then pull the information back. Using tags, we can extract information, and as a community organize the emerging folksonomy

This blog post brings together two long-standing interests of mine. The first is how to script web tools to support small-group collaborative learning, and the other is how to support reorganization of ideas across groups.

Two meanings of the word "scripting"

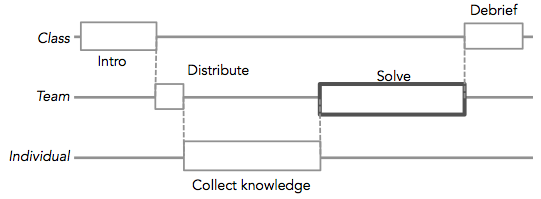

There is an interesting intersection between two quite different meanings of the word scripting in the context of my work. In the CSCL literature, scripts refer to sequences of activities that support groups of students in carrying out a collaborative learning activity. They can be very simple and generic, like the well-known jigsaw script, or very content-specific. There is active on-going research on scripting, including how external scripts interfer with internal scripts, and the dangers of over-scripting.

From the technology side, we talk about writing scripts as a light-weight form of programming, to ask the computer to do something for us. Scripting a program, or a web site, means that we can interact with it automatically, for example asking Google Docs to set up 20 documents for us. There is obviously a connection between developing educational scripts and actually "implementing" them in technology. Often, specialized software has been written to enable specific scripts, but there has been some attempts at enabling more generic implementations of learning designs into software.

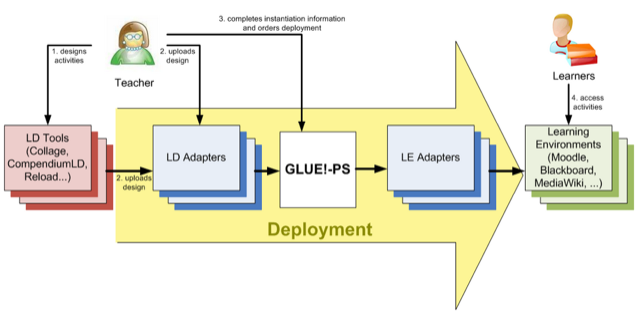

One inspiring example for me has been GLUE-PS (paper), which can take a learning design from a learning design software, like CompendiumLD, and set-up the necessary software, for example pre-generating Google Docs and wiki-pages, splitting students into groups, and assigning different resources to different groups, etc.

Etherpad for collaborative writing, and more

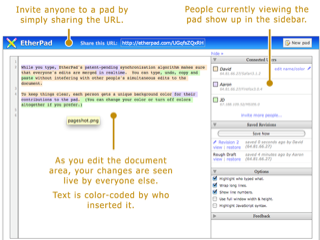

For those who have not heard of, or used, Etherpad, I always introduce it as "like Google Docs". It enables very easy collaborative editing of documents, where everyone logged in immediately see all changes made by other users. It features very light-weight formatting, and is not designed to generate print-ready documents, but is perfect for brainstorming, note taking, etc. It also focuses more on the live-editing situation, with the text written by each user colored differently. It can be quite mesmerizing to see a document being filled in by multiple people at the same time.

For those who have not heard of, or used, Etherpad, I always introduce it as "like Google Docs". It enables very easy collaborative editing of documents, where everyone logged in immediately see all changes made by other users. It features very light-weight formatting, and is not designed to generate print-ready documents, but is perfect for brainstorming, note taking, etc. It also focuses more on the live-editing situation, with the text written by each user colored differently. It can be quite mesmerizing to see a document being filled in by multiple people at the same time.

We often used Etherpad for collaborative meetings at P2PU (case study), and I also had some interesting experiences using in the P2PU course "Intro to Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning". We began by chatting in the chat feature, but gradually migrated over to use the main editing space, which enabled us to keep multiple separate discussions going simultaneously. I have written and [spoken]( about this experience, and it's something I'd love to experiment more with.

We often used Etherpad for collaborative meetings at P2PU (case study), and I also had some interesting experiences using in the P2PU course "Intro to Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning". We began by chatting in the chat feature, but gradually migrated over to use the main editing space, which enabled us to keep multiple separate discussions going simultaneously. I have written and [spoken]( about this experience, and it's something I'd love to experiment more with.

For a large course I am currently helping teach, we began by using Etherpads to support note-taking in small group discussions. Setting up 10-15 Google Docs, remembering to set the sharing options correctly, and copying and pasting the URLs to the wiki was a lot of work, and it was much easier to do it with Etherpad. The students all found Etherpad very easy to use, and it was nice to be able to pull up group notes on the projector afterwards while groups were presenting their ideas to the rest of the class.

Scripting Etherpad

Etherpad has a nice simple API, which let's you create new pads and fill them with content, and read the content of existing pads. (Since there are no permissions or logins, that's basically all the actions that you would need). Since Etherpad conserves the full history of all changes, you can also access older versions of a pad. Here is how little code you need to get started.

A simple helper function to execute Etherpad API calls, and properly format the return message:

def run_etherpad(path, **params):

params['apikey'] = settings.ETHERPAD_API

data = urlencode(dict(params)).encode('ascii')

url = ("%s/api/1.2.10/%s" % (settings.ETHERPAD_URL, path))

r = json.loads(urlopen(url, data).read().decode('utf-8'))

return(r)

And then I can simply execute any of the API commands listed in the Etherpad documentation, for example:

text = run_etherpad("getText", padID=pad)

The first thing I did with this, was to write a little script that took a template (typically a few questions for discussion), and created a number of identical pre-populated Etherpads for the discussion groups. It then generated an HTML page with all the links, which I could copy and paste into the course wiki. This already saved a lot of time. Given that we now have a list of all the Etherpads, it's just as easy to pull all the text from the Etherpads back into a script, and do something with it.

For example, I can generate a quick HTML page consisting of the text from all of the Etherpads together, which makes it much faster to quickly scan through what groups have been doing, rather than opening 15 tabs in the browser. Or I can automatically pull each group's page and post it to the wikipage of that group for easier access in the future (Etherpad is great for live editing, but not very trustworthy as a long-term repository of information).

Using tags to extract and organize ideas

A little detour about making ideas moveable, supporting organizing and synthesis

One of the things we found from teaching this course last year, is that the ideas and information entered tended to be "stuck" on the week and group-specific pages. After several weeks of the course, we would have lot's of great reflections, notes from readings, project ideas, etc., but they were not organized in a way that was easily accessible to the students. When working on their final projects, the students were more likely to use Google, rather than accessing the common knowledge base which we had tried to structure throughout the course.

I have long been inspired by a course that I took in the first year of my MA, which used an environment called Knowledge Forum. I made a screencast to showcase the course, and how the environment enabled us to go back to our old notes, reorganize them, and see new connections and gaps. At that time, I contrasted it with threaded discussion forums, where a post is usually "captured" in the chronology/thread where it is posted.

I have long been inspired by a course that I took in the first year of my MA, which used an environment called Knowledge Forum. I made a screencast to showcase the course, and how the environment enabled us to go back to our old notes, reorganize them, and see new connections and gaps. At that time, I contrasted it with threaded discussion forums, where a post is usually "captured" in the chronology/thread where it is posted.

Inspired by this course, and by workshop methodology, I began thinking about what I called "the cycle of divergence an convergence" which I began exploring in a talk and a paper. I also thought that tagging could be a low-tech way to enable "movable ideas". An example script could be the following: after a class had discussed a topic for a few weeks, each week with a new "input" (stimulus), they could collectively or individually decide on a few emerging overarching themes, and go back through the posts, tagging them accordingly. The discussion forum software would then create "saved searches" for these tags -- dynamic folders containing all the posts tagged with a certain tag. Students could then revisit these posts in a new context, continue the discussion, etc.

Inspired by this course, and by workshop methodology, I began thinking about what I called "the cycle of divergence an convergence" which I began exploring in a talk and a paper. I also thought that tagging could be a low-tech way to enable "movable ideas". An example script could be the following: after a class had discussed a topic for a few weeks, each week with a new "input" (stimulus), they could collectively or individually decide on a few emerging overarching themes, and go back through the posts, tagging them accordingly. The discussion forum software would then create "saved searches" for these tags -- dynamic folders containing all the posts tagged with a certain tag. Students could then revisit these posts in a new context, continue the discussion, etc.

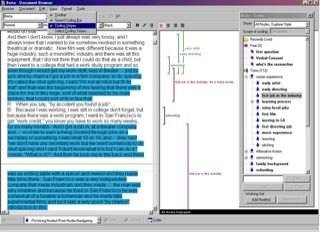

This turns out to be very similar to the process of qualitative research, and a methodology supported by tools like NVivo (good video intro), where one codes individual pieces of text, and then pulls up a list of all the coded pieces for a given code, to see them in a new context. Something that might be useful for quantitative research, for organizing a literature review... and for supporting community knowledge and deep thinking in a collaborative learning situation?

This turns out to be very similar to the process of qualitative research, and a methodology supported by tools like NVivo (good video intro), where one codes individual pieces of text, and then pulls up a list of all the coded pieces for a given code, to see them in a new context. Something that might be useful for quantitative research, for organizing a literature review... and for supporting community knowledge and deep thinking in a collaborative learning situation?

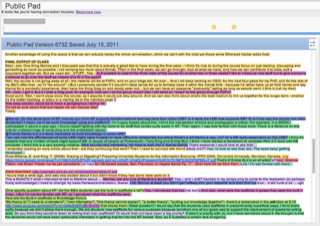

Tag-extract, short recap

Programmers both like to reinvent the wheel, and to scratch their own itch, so faced with a large amount of notes that I needed to structure into a literature review, while keeping the source-information (which paper did a certain idea come from), I experimented with tagging. (Adding some markup to the text, and then processing it with a script, is far easier than developing a new graphical interface for tagging). I had three simple rules, or principles, which turned out to be quite powerful:

Programmers both like to reinvent the wheel, and to scratch their own itch, so faced with a large amount of notes that I needed to structure into a literature review, while keeping the source-information (which paper did a certain idea come from), I experimented with tagging. (Adding some markup to the text, and then processing it with a script, is far easier than developing a new graphical interface for tagging). I had three simple rules, or principles, which turned out to be quite powerful:

- all the text below a source indicator "belongs" to that source, and will always be tagged as coming from that source

- any tag applies to the line it is on

- all text indented below a tagged line, belongs to that line

I wrote a detailed blog-post about this tool, complete with an extensive screencast, showing the tool embedded in an academic workflow process, and a more focused screencast focusing on the tool itself.

I wrote a detailed blog-post about this tool, complete with an extensive screencast, showing the tool embedded in an academic workflow process, and a more focused screencast focusing on the tool itself.

At the top, you see a text file with notes, and bibdesk-identifiers as the "source". After adding tags, and running the script, I get the output seen on the right, where the notes are reordered according to tag, but with the source still there. When writing about for example metalearning, you then have all the relevant ideas/quotes, together with the article citations. Here's an example of raw sorted notes about open courses, and here the resulting draft.

Bringing all the pieces together

So we have introduced the idea of pedagogical scripting, as well as implementing scripts in computer code. I've discussed the desire to make ideas more "moveable", and support deeper work on ideas, and talked about the idea of using tags to support this. Finally, I introduced the tool tag-extract, which I developed to work on a literature review. This blog post is already long enough, so I will write a separate blog post about the actual design, implementation and evaluation of the pedagogical script using these ideas.

The script flowchart is from an unpublished manuscript by Pierre Dillenbourg. The GLUE-PS image is from the GLUE-PS website, the concept map about concept maps from the Cmap site, and the NVivo image from the NVivo primer

Stian Håklev October 3, 2014 Toronto, Canada comments powered by Disqus