Learning idiomatic Haskell with Exercism.io

March 11, 2014, [MD]

I got my introduction to functional programming through Clojure, but lately I've been really fascinated by Haskell. I gave up on it a few times, because it can seem quite impenetrable, and very different from anything that I'm used to. But there is something about the elegance, and powerful ideas that keeps me coming back. I've read a bunch of tutorials and papers, followed blog posts, and experimented a bit with ghci and IHaskell, but I never really got off the starting block with writing my own Haskell.

How to get practice?

The projects I'm currently working on in Python are too complex and urgent for me to try to implement them in Haskell at this point, and because Haskell is so different, I found myself stymied doing even simple things, even though I'd just finished reading a complex CS paper about monads. I needed some structured tasks that were not too hard, and that gave me good feedback on how to improve.

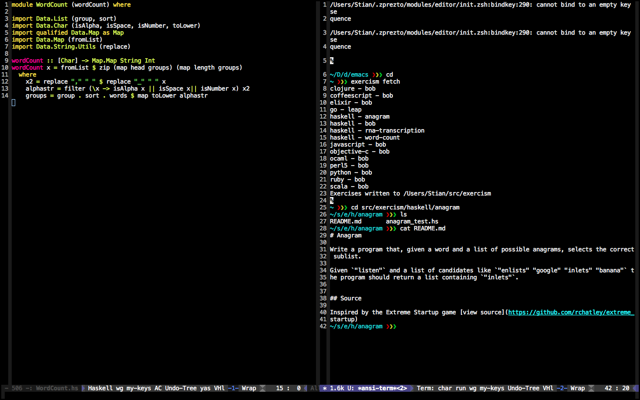

Listening to the Functional Geekery podcast, I heard about exercism.io, which provides exercises for many popular languages. There are several similar websites in existence, perhaps the most well known is Project Euler, however that focuses too much on CS/math-type problems, and is perhaps better for learning algorithms than a particular language. The way exercism.io works, is that you install it as a command line application. The first time you run it, it downloads the first exercise for a number of languages.

The exercises themselves consist of test cases, and it's up to you to write a module that will fulfill the test case. Once you are done, you use the command line client to quickly submit the answer, which unlocks everyone else's answers, and downloads the next exercise. The fact that you download the test cases and README files, and work on your local computer, is also great. You can use the environment you're used to (Emacs, VIM, EclipseFP), with all the tooling, documentation, autorunning tests, etc., that you are used to.

Trying before being told

This kind of graded approach is brilliant, because it precludes "cheating". It's easy to skip ahead to the solution, say "that makes sense, I would have come up with that", and move on. But it's important to actually force yourself to come up with that. Reading other people's versions, and the feedback they received, after having struggled with the problem yourself, is also incredibly informative -- and again, I think you get far more out of it, than just browsing through solutions before you've put in the hard work yourself.

There's a parallel to some of the work I'm doing with audience response systems in lectures. Eric Mazur at Harvard puts physics problems on the projector, and asks students to first try to solve them themselves. Then they have to try to convince the person next to them about the right answer, which they submit by clicker. Finally, he explains and discusses. Students who have wrestled with the problem for a while already, and been exposed to other people's ways of thinking, are far more receptive and learn more from the final explanation, than if you had just gone directly to lecture.

Idiomatic code

The objective is not just to pass the tests (which is in most cases trivial, for example it would not be difficult to write very specific code that just fulfills the test cases, but does not generalize), but to write as beautiful, idiomatic code as possible. One might start with an inelegant approach that fulfills the test cases, and then begin refactoring into something one can be proud of, while making sure the test-cases continue to work.

This is an interesting challenge, and it's also very useful, because one of the biggest challenges when learning a new language is internalizing the metaphors and idioms of that language. When writing a simple function, there might be many ways of writing it, that will all "work", and yield the same result. Yet once you begin writing larger and more complex programs, programs that need certain kinds of performance (memory, CPU, dealing with very large inputs etc), the difference between different approaches becomes very large.

The first project I did was quite embarassing. The task asks you to construct a function that takes a string, and generates a string as a response. There are a bunch of test cases, and you have to figure out yourself how to group them (seems like strings ending with ? are questions, but not if they are all upper-case, etc). I decided to use pattern matching, which was a fair approach.

However, I instinctively used regexp patterns to match the text, instead of looking for built-in functions. I got it to work mostly (and did learn how to use regexp in Haskell, which I hadn't used before), but I had problems with unicode, and spent too long trying different patterns. After I submitted, I saw an incredibly elegant solution, using only built-in predicates like isAlphaNum, which read and compose much better than my convoluted regexps. A very good lesson, and one I internalized much quicker than if I read a blog post about it, without having struggled with it myself first.

Future growth of exercism.io

The platform is quite young, and I'm wondering how it will scale. For the first few exercises in Haskell, there were only about 15 responses (since you cannot proceed until you have submitted the first few responses, I'm guessing the more advanced exercises will have even fewer answers). If there were hundred answers for a given problem, I might want to see as many different approaches as possible, not 20 examples that are basically the same (I'm also interested in as much diverse feedback as possible).

Perhaps some kind of voting feature is necessary. There is the possibility of providing feedback to individual submissions, and while I really appreciate people's feedback, I almost feel like it isn't necessary once I've seen other people's contributions -- I already have a good idea of what I could do better. (There are only so many different ways of doing these fairly small and bounded problems).

Anyway, I was very excited to discover this platform. After the first task, which I spent about two hours on, I did two more. With these, I was less embarassed when seeing other people's code, but in both cases, there were more elegant solutions than the one I suggested. One of the recurring themes also seems to be really understanding the core library, and all the functions that are already implemented, instead of trying to reinvent the wheel.

Go learn some code!

Stian Håklev March 11, 2014 Toronto, Canada comments powered by Disqus