Parsing massive clicklogs, an approach to parallel Python

March 10, 2014, [MD]

I am currently working on analyzing MOOC clicklog data for a research project. The clicklogs themselves are huge text files (from 3GB to 20GB in size), where each line represents one "event" (a mouse click, pausing a video, submitting a quiz, etc). These events are represented as a (sometimes nested) JSON structure, which doesn't really have a clear schema.

Introduction

Our goal was to run frequent-sequence analyses over these clicklogs, but to do that, we needed to process them in two rounds. Initially, we walk throug the log-file, and convert each line (JSON blob) into a row in a Pandas table, which we store in a HDF5 file using pytables (see also). We convert the JSON key-values to columns, extract information from the URL (for example /view/quiz?quiz_id=3 results in the column action receiving the value /view/quiz, and the column quiz_id, the value 3. We also do a bit of cleaning up of values, throw out some of the columns that are not useful, etc.

Speeding it up

We use Python for the processing, and even with a JSON parser written in C, this process is really slow. An obvious way of speeding it up would be to parallelize the code, taking advantage of the eight-cores on the server, rather than only maxing out a single core. I did not have much experience with parallel programming in general, or in Python, so this was a learning experience for me. I by no means consider myself an expert, and I might have missed some obvious things, but I still thought what we came up with might be useful to others.

There are many approaches to parallelizing code, and choosing the right one requires thinking about your algorithms -- which functions need access to shared state (and can you design it so that you minimize shared state), are you CPU-bound, or IO-bound, what is the grain size that it makes sense to split at, etc.

Shared state

I was using HDF5 as my storage format, and pytables can append to an existing table. Theoretically, one would think that the lines in the log file are completely independent from each other, just get them converted and into the HDF5, and once you've got them all entered (appended), you can index and sort by timestamp, username, etc. However, Pandas Data.Frames have one big limitation compared to R data.frames -- no categorical column type. In R, a data.frame might have a column that stores the answer to a likert-type question (Not at all to Totally agree, for example), and even though there are 10,000 rows, those five text answers are only stored once, with each cell only containing a pointer to the correct alternative. This makes the table take much less space.

Pandas was developed for financial analysis, and still seems fairly focused on numbers. (It also builds upon NumPy, which also doesn't have a categorical format). In our case, this was a big problem, since the difference between storing "/view/lecture" (13 bytes) and 1 (1 byte) for a table with 14 million rows is huge! (Especially when you consider that Pandas does much of its work by loading the entire table into memory).

I decided to hack my own little categorical format, by creating a memoize function, which would assign a unique number to each new value it was called with, but always return the same number for the same value. Quick example:

memoize("hello") # => 1

memoize("how are you") # => 2

memoize("hello") # => 1

memoize("how are you") # => 2

memoize("i'm fine") # => 3

Initially the function simply kept state in a Pandas Series, and once I had finished parsing the entire clicklog, I wrote these series to the same HDF5 file (HDF5 files can contain multiple tables, files etc). This worked great, and it meant that instead of this:

{"key": "user.video.lecture.action","value": "{\"currentTime\":257.066689,

\"playbackRate\":1,\"paused\":false,\"error\":null,\"networkState\":1,

\"readyState\":4,\"eventTimestamp\":13752243249891,\"initTimestamp\":

137524554345511,\"type\":\"ratechange\",\"prevTime\":227.066689}","username":

"9930a0523403499b7347707c92bccbcbff1a","timestamp": 13752234234277,"page_url":

"https://class.mooc-platform.org/course-001/lecture/view?lecture_id=31","client":

"spark","session":"30423409-1323423042304","language": "en-US,en;q=0.5","from":

"https://class.mooc-platform.org/course-001/lecture/view?lecture_id=31",

"user_ip": "123.255.122.167","user_agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; rv:22.0)

Gecko/20100101 Firefox/22.0", "12": ["{\"height\":678,\"width\":1207}"], "13": [0]}

...I ended up with what was externally represented as a list of 18 floats (I wanted to store them as integers instead, but Pandas needs floats to be able to represent NaNs, which was important, given that many of the values were sparse).

The problem with shared state

This worked well before I tried to do any kind of speedup (apart from the fact that the script took 12 hours to run on the largest file). However, I wanted to be able to iterate a little bit quicker, and explore ways of speeding up the code. Because I needed to keep the memoized data consistent, I couldn't just fork off a bunch of processes that each would process their own data -- they would have all ended up with their own individual memo tables, where 1 corresponds to hello in one process, and what's up in another. To address this, I moved the memoization code out of the function that processed individual lines, and applied it to each Pandas column in a final step before appending the processed chunks to the HDF5 file.

The function to process each line should now be a pure function -- that is, a function that always returns the same output given the same input, not reliant on any external state, etc. -- and thus ripe for parallization. I tried using pool.map from the multiprocessing library to let the computer automatically figure out how many external processes to run, etc. Here I ran into a problem of grain size... It takes a bit of time to fire up processes, transfer state, coordinate across threads etc, so if you assign each process too little work, the gain from having work done in parallel is more than lost. This was the result -- my naive attempt led to a slowdown. (Some libraries try to tackle this automatically and figure out the correct grain size, but pool.map didn't seem to be able to).

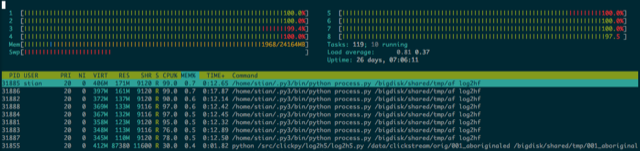

My second attempt was to do the chunking myself -- I read in 100,000 lines, chunked it into chunks of 20,000 lines, and then mapped over this list of lists. This worked better, but I only saw a small speedup (maybe 50%). Partly because of the extra time spent chunking lines, and partly because a big part of the program was still spent converting the list of dicts to a Pandas DataFrame, memoizing the columns, and writing to file (I could see this very clearly by monitoring top -- first you see five processes maxing out their respective cores, and then suddenly they drop away, and there is only one process on one core working).

Map-reduce

A very common paradigm for cluster computing (with multiple computers) is called map-reduce. Basically, you split the data into chunks, run parallel operations on each chunk, and then somehow "reduce" the result back together. An example could be getting number of page views per URL for an extremely large clicklog, have each serve count up clicks per URL for a piece of the log file, and then have a script that combines the numbers in the end.

Something similar can be done on a single computer, and for the second phase of the analysis, this is what I ended up with. The second phase, after we got the nice HDF5 file, is to do some processing for each user. Instead of the fact that a user watched video 39, we want to know if he/she watched the video for the first time, or if it was an immediate review, to be able to compare patterns across students, and even across courses.

This means that we cannot treat each student event individually -- we need to know which videos the students has already seen, etc. However, we can treat each student individually -- how one student's actions are tagged, are not at all reliant on other students' actions.

Split, process, collect

One very nice thing about HDF5 is that once you've indexed the table (which is quite fast), you can read in data based on simple queries. Thus, once we've opened the HDF file with store = pd.HDFStore("hdfstore.h5"), we don't have to read the entire table into memory with db = store['db'], which might take 6GB of memory (with a big table), but we can instead run

user = store.select('db', pd.Term('username = 3434')

(in our case, we also select on timestamp, because we only want events that happened while the course was active). Add to this that pytables is thread-safe for reading (ie. multiple processes can read from the same file, without problems), but not for writing (it's not like a mysql database that can have multiple processes writing at the same time).

So instead of having one script that tries to parallelize subtasks, what I ended up doing was to run eight Python scripts concurrently. I simply indicate as a command parameter which usernumber to start with, and how far to jump each time. Thus, the first Python process starts with user 1, then does user 9, user 17 etc, until there are no more users. The second process starts with user number 2, then 10, etc. This way all users get processes, without the need for any coordination. Initially I started the processes from a shell script, but then I put it into Python:

print("Spawning %d processing scripts" % numprocesses)

procs = []

for proc in range(1, numprocesses+1):

range_start = proc

range_jump = numprocesses+1

procs.append(Popen([python_exec, "videos_reduce.py", hdffile, str(range_start), \

str(range_jump), tmpdir, cutoff]))

I can then wait for all processes to finish, and then do any cleanup work that is necessary.

def all_procs_finished(procs):

for proc in procs:

if proc.poll() == None:

return False

return True

while not all_procs_finished(procs):

time.sleep(5)

Reduce

Initially, I wanted to capture the output in a new HDF5 file, so I had the individual scripts dump their output pickled into temporary files (named using uuid) in a temporary directory, which would then be read by the main script, and appended to the HDF5 file (thus ensuring that only one thread wrote to the HDF5, to avoid data corruption). Later, we decided we wanted to output a text file for processing in R, which made it even easier. The individual thread simply spit out a bunch of text file chunks into a temporary directory, and then we combine them with cat * > outfile.

This approach worked swimmingly. Since we are just running the same script eight times in parallel, it's easy to debug by running the script only once (I would run it with 1 10000 to start with user 1 and jump 10000 ahead, to 10001, 20001 etc until the file had been exhausted). Because all the hard work was done in the individual threads, I got very close to 100% utilization on all eight cores for the duration of the run (which is a beauty to see in htop), and even when running a separate process that collected the output files and wrote them to HDF5, that process used so little CPU as to be negligible.

But what about that shared state?

At this point, I needed to go back to the initial phase to redo a bunch of the parsing, because I had received new files. Inspired by my experience with the second phase, I thought about how I could improve the first-phase scripts. The tricky problem was how to coordinate state. I did a bunch of googling to look at "coordinated / parallel memoization libraries for Python", and somehow came upon people using Redis for that purpose.

I had heard very vaguely about Redis, but never known much about it. It turned out to be perfect for the job through. It's basically a very fast distributed key-value store (although it also has other value types, like lists and hashes), with an API that only takes a few hours to learn. I installed a Redis server, and rewrote my memoization function to use Redis instead of the Pandas Series, with only very minimal changes.

Here is a shortened version of the memoization class:

class Memo(object):

def __init__(self, name, prefix):

self.r = redis.StrictRedis(host='localhost', decode_responses=True)

self.name = name

self.prefix = prefix

self.counter = '%s:%s:cnt' % (prefix, name)

self.store = '%s:%s:store' % (prefix, name)

if self.r.zcard(self.store) == 0:

self.add_object('None')

def add_object(self, obj):

c = self.r.incr(self.counter)

self.r.zadd(self.store, c, obj)

return c

@lru_cache(maxsize=256)

def get(self, s):

if s is None or pd.isnull(s):

return -1

existing_score = self.r.zscore(self.store, s)

if existing_score:

return existing_score

else:

c = self.add_object(s)

return c

You create a new Memo class with a name, and then just call it like described above. lru_cache, from functools, is really neat - it remembers the last n (maxsize) arguments to the function, and their return values, and if you call the function with an argument in the list, it gives you the response, without having to run the function. This is safe, given that once a value is assigned in Redis, it will never change. Having this meant a big speedup (especially since it's very common for adjacent lines to have similar values, for example a chunk of lines all from the same user, etc), however when I tried to set maxsize=None, ie. to remember all the values, it became much slower. Apparently Redis is much faster at looking up a hash-value among 10,000 than Python, despite the overhead of calling out.

So the final version of the script does several thing. It begins by running the shell command split -n, which splits the log file into chunks based on number of lines (currently 40,000 lines seems to be a good size). It does not wait until cut is finished, but begins immediately launching the 8 processes, which begin reading the next available file in the temp dir, and processing it.

The eight workers pick up a temp file "chew on it", and spit out the result as a pickled array of dicts in another temp dir. The master script, having launched all the processes, begins to cycle, waiting for files to appear, reads them in, and appends them to the HDF5 file. The worker processes continue until they've gotten the signal that cut has finished (through Redis), and there are no more files. The master script continues until all worker processes have finished, and there are no more "chewed" files. It then repacks the HDF5 file (to add indices), and adds the memoized data from Redis.

Using this approach, I am now able to process a 20GB clicklog file in 12 minutes! (Resulting in a 3.5 GB HDF5 file with something like 14 million events).

Stian Håklev March 10, 2014 Toronto, Canada comments powered by Disqus