tag-extract: A tool to automatically restructure text/outline using tags

June 13, 2012, [MD]

I created a tool that can reorganize an outline in text format with simple @tags, using the hierarchical format of the file to "intelligently" group subcategories together, and tag lines with their top-level category. I provide examples of how this can be used for a literature review, or for qualitative research.

Moving ideas around

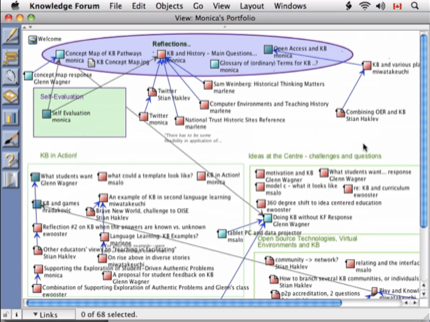

I've long been interested in ways of working with ideas, texts, and notes – collecting them and reorganizing them – see for example my section on this in "Grappling with ideas". My experiences with Knowledge Forum (mentioned in the link above) taught me the importance of being able to "move ideas around", rather then having them fixed wherever they happened to be first entered. I've also been very inspired by experiences in physical workshop settings, writing down ideas on sticky notes and moving them around as new categories emerged, for example.

But in fact, this goes further back then that. I remember in my first year as an undergraduate, as we had to read papers, and write essays, and I gradually developed a technique of studying that fit my own style. I never liked using yellow markers on our reading packages, because I felt that these highlights would be "trapped" inside the different papers. Instead, I would read the papers and take copious notes on my laptop, in a very informal manner, with many abbreviations, for example:

Johnson (1999)

p 5. diff. betw. CIDA and USAID

p 6. USAID & support US farmers

p 11. food aid -> depressed food

prices in dev'l countries (see Wilkensky), IMF

In this way I quickly captured the important points of the article, and in a format which was "fungible". Later, when I sat down to write the paper for class, I would have several text edit windows, create headings, and copy lines over to different topics, for example:

Corruption:

Johnson 1999 p 6. corruption decreases

mostly linearly with GDP growth

Peterson 2011 p 17. corruption is linked to

social history, and not connected to economic growth

Good governance:

Alfanski, 1997 p 10. good governance became

an IMF priority in 1990's

etc. (here are the actual notes I took for the essay back in 2004). This took a while, and was all manual - I copied the individual lines, and had to add the article they came from. But the advantage was that once I had gone through and classified all my notes like this, I then had my "outline", and could write my article, first writing about corruption, and quickly able to insert the relevant citations, then about good governance, etc.

I remember fantasizing about creating a tool which would let me tag a text string with the property of being from a certain publication, and when I copied a part of that text to another place, that "property" would follow the text, kind of like how you mark a paragraph as blue, and when you copy a few words from that paragraph and put them somewhere else, those words stay blue. Little did I know that I would create a tool to essentially do that (although slightly differently), 8 years later.

Using tags to move things around

The example of a workshop with sticky notes, and Knowledge Forum, are both examples of "graphical interfaces" where you can literally move ideas around, and organize knowledge spatially. I find these kind of interfaces very fascinating (although ironically, I don't regularly use any concept mapping, mind mapping or other graphical idea tool). However, for someone who likes hacking, one of the challenges for me is that it's much easier to write tools to process straight text, than it is to program a graphical interface.

I first had the idea of using tags to help us reorganize ideas, and make them "fungible" when thinking about Pepper (formerly Knowledge eCommons), a discussion forum tool developed at OISE, and how we could more easily work with the ideas posted, and reorganize them (for example going back after five weeks of discussions, captured in five weekly forums, to extract all the posts about a certain topic into a new forum, to continue the discussion there). This made me realize that tags could be used in many different ways. If I tag a blog post immediately upon writing it, or a Flickr photo immediately upon uploading it, it's an example of a folksonomy. It doesn't use a controlled vocabulary, so there might be some photos tagged "Istanbul", some tagged "Turkey", some tagged "Стамбул" etc, and the person tagging also has to try to "predict" which words a future user will search for.

Contrast this with for example tags on Twitter. Often times, these function more as channels (and indeed the # symbol comes from the channel prefix used on IRC). If I tag something with #oa, I know that a number of people have saved searches for #oa because they are interested in Open Access. This becomes even more clear when you're attending a conference that has designated an official Twitter hashtag. In many ways, this is like a global "category", more than a folksonomy tag.

So with regards to the discussion forum, my idea was not for people to try to predict what people were going to be searching for in the future, and tag messages immediately as they wrote them. Instead, people would revisit the group's writings after a certain period, and find certain emerging topics. They could then apply a tag to messages that they wanted to "collect", and a new saved search would automatically be created for this tag, where all messages could be seen together, and the discussion could continue.

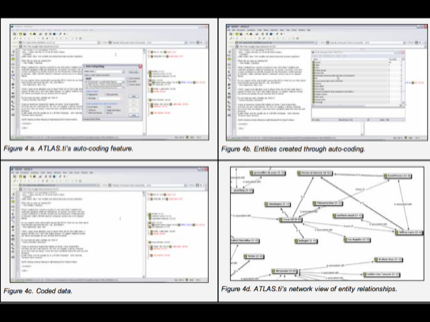

In many ways, this concept of emerging ideas or categories reminds me of grounded qualitative analysis, when someone is coding a bunch of interviews, and reads them over and over again. He or she doesn't start out with set categories, but gradually certain trends emerge, and the different statements are sorted - whether by moving piles of cut-up text slips, or using some kind of qualitative research software.

This is again quite similar to the process of doing a literature review. You start by identifying a large amount of articles in a specific field, and through reading them you start identifying certain trends or categories. Then you need to move and organize your notes according to these trends, before you can start writing the actual literature review article.

Building the tool

With all this in the back of my mind, I was working on a literature review of research on open courses (there have been many articles on Open Educational Resources, but very few on open learning interactions). I began finding and adding PDFs to my system, reading them and extracting highlights, adding high-level notes using sidewiki. But I was left with a long list of individual article notes - how to turn this into one document?

On a hunch, I decided to try to use Taskpaper, a text-based outliner, to take very brief notes from each paper (also capturing the citekey as header). Part of the file ended up looking like this

Now I at least had all the notes in one file, as opposed to spread over forty wiki pages. But still, I had to do what I did when writing the political science article in 2004, copy and paste lines from each article to sort similar ideas together. I decided that if I could just tag lines with the name of the grouping, and have a script move the lines for me, that would speed the process up considerable. So I wrote tag-extract.

Taskpaper makes tagging even easier by automatically recognizing words after @ as tags, color coding them red, and enabling tag-completion based on the tags you've already created.

I further realized that given the structure of this text file, there were two things that the script could assume. The first was that every line below a cite key like [@weller2007distance] "belonged" to that citekey, so it could automatically append this citekey to tagged lines. Secondly, text indented below a line in a certain sense "belongs" to that line, so if that line gets tagged, all the text indented below should be included as well. In the example below, the entire list of theories will be copied to the section called "theory", but certain lines in the list will also be copied to other tags, like "connectivism" and "andragogy".

When it comes to output formats, I so far added three different output formats (although it would be easy to add other ways of formatting the text). The simplest one is a new indented text file, which can be read by Taskpaper or even a normal text editor.

Above you see two tags from the output file, @soc_contract and @metalearning, underneath you see the lines tagged, and the citekeys they came from. Below, you see the same section in a text editor (Taskpaper works on pure text files, it simply recognizes and auto-formats certain aspects).

In addition, you can output with Dokuwiki markup, and here you can see my entire literature review notes, sorted.

However, to me it was really the final format that made all the difference. My favorite tool for authoring academic texts is Scrivener, and I used it to write both my BA honors thesis and my MA thesis, as well as a number of articles. From my MA thesis, I even published all the raw notes from Scrivener. The great thing about Scrivener is that you can easily keep all your notes in the same document as your actual text, and view both the text for a section you are writing, and the notes for that section, in a split screen window. So I created an export format that generates a folder with one text file for each tag.

This can then be dragged and dropped onto a Scrivener document.

...and you can start writing. You've got all your notes, separated into sections which corresponds to the sections you are going to be writing in the actual document, and you've got the citekeys, which you can just insert directly into the draft. Here's an example of my writing the literature review.

Once you are finished writing, you can export the Scrivener document back to Dokuwiki, which formats it nicely and renders all the citekeys as proper citations (you can see the current, very early draft)

...with an automatically generated bibliography...

All in all, a very neat workflow. The script itself is not very advanced (although it still took me a bit of fiddling to get it all to work), but I really like the way it lets me work. It's fairly decoupled from researchr, so it should be quite easy to get it to work for others as well (note, it requires Ruby 1.9.1 because of the way I did the regexps).

I made two screencasts to show how this works, the first is a brief five minutes, and shows the basic functionality of the tagging with two examples, one a literature review, and the second coding interviews (given my thoughts of how this overlaps with qualitative research - although I'm not claiming that this is a competitor to ATLAS.ti exactly)

The second is a longer 18 minutes, and goes through the entire process of creating a literature review, starting with extracting information from articles, and ending with publishing it back to the wiki. It showcases much of the functionality of researchr, but with a much more task-specific focus than my first screencast, almost a year ago.

Stian //Update, on January 31, 2020, I changed the links to the literature review to point to Roam Research, where I've imported them. My wiki is no longer online, but all the information is in that Roam Research database.//

Stian Håklev June 13, 2012 Toronto, Canada comments powered by Disqus