OpenEd: Week 1

August 31, 2007, [MD]

QUESTIONS:

In your opinion, is the “right to education” a basic human right? Why or

why not? In your opinion, is open access to free, high-quality

educational opportunity sufficient, or is it necessary to mandate

education through a certain age or level?

I was excited to enter this course, because in addition to being very passionate about the topic, I was also interested in the method of teaching/taking the class. If I want to understand what different methods of distance/open education work, I cannot just read about other people’s experience, I need to try it out myself. And this first week of the course has been very interesting - while the readings themselves were rather dull, they did provide a good background and “common base”, but it was the comments from my fellow students that sent me off reading, and made me both remember old ideas I’ve had myself, and made me explore new thoughts. In a way, I actually feel closer to my students in this class, than most of the ones sitting next to me in a hundred-person lecture theatre at University of Toronto, because there all we do is listen to the same lecturer drone on, and then we go home and study for the exam. Here we share our reflections, based on our own ideas and previous experiences, which makes the learning experience much more interesting and personal.

It also makes it much harder for me to answer this week’s questions. After reading the allotted readings, I was going to give quite standard answers, however after reading other people’s answers and thinking, it became much more complex. The two Tomasevski readings stated three things very clearly, that primary education should be free of charge, compulsory and not exclude anyone. It then went on to discuss the legal and economical obstacles, spending very time problematizing what was meant by primary education. Many problems were touched upon in a summary matter, but not explored further - I think they are very much worth exploring however.

Language

of education/local content\

If we first accept the idea that for children to attend an institution

that is a “primary school” is generally a good thing, then there are

still a number of things I wanted to comment. First of all, the matter

of language of education is essential, and it is only briefly touched

upon in Tomasevski. Birgit Brock-Utne has

dealt extensively with this topic in her great book Whose Education for

All, the recolonisation of the African

mind, and

in numerous articles. She is very sceptical to many of the thoughts

propounded in Tomasevski’s article, and contained in the Jomtien

agreement. Education is

far from neutral, and when it is conducted in a foreign language, and

with a curriculum that has no relation to the local people’s situation,

it can be downright damaging. She gives the example of a little girl who

has a multiple choice test (I hate multiple choice!) being asked which

of these four French guys first discovered a given waterfall. She

answered E, none of the above, because her family had lived by that

waterfall for several hundred years. She got an F.

Language

of education/local content\

If we first accept the idea that for children to attend an institution

that is a “primary school” is generally a good thing, then there are

still a number of things I wanted to comment. First of all, the matter

of language of education is essential, and it is only briefly touched

upon in Tomasevski. Birgit Brock-Utne has

dealt extensively with this topic in her great book Whose Education for

All, the recolonisation of the African

mind, and

in numerous articles. She is very sceptical to many of the thoughts

propounded in Tomasevski’s article, and contained in the Jomtien

agreement. Education is

far from neutral, and when it is conducted in a foreign language, and

with a curriculum that has no relation to the local people’s situation,

it can be downright damaging. She gives the example of a little girl who

has a multiple choice test (I hate multiple choice!) being asked which

of these four French guys first discovered a given waterfall. She

answered E, none of the above, because her family had lived by that

waterfall for several hundred years. She got an F.

Brock-Utne’s argument is that you cannot just start by funding only primary schools, and then later switch to universities, because who will teach in the primary schools? Who will develop the text books in local languages, highlighting local knowledge, understandings of history, society and politics? Without all these, the primary education is not much worth. (She also comments that many of the literacy surveys of international organizations actually only measure literacy in the colonial language, whereas the rate in the local languages might be much higher). (Talking about languages, I have to share this link to what an elementary school in multicultural Minnesauga, Canada is doing - it’s a wonderful approach, making all the students feel really welcome - like assets and not burdens - and enrichening all the other students. I wish I could be a student/teacher at that school!)

The

right to refuse?\

Greg

Francom

makes an interesting point about “the right to refuse” for for example

indigenous people. I think this is a very interesting point, and I have

two examples. When I was in Laos, I joined an organized walking tour

into an indigenous community. They lived a day’s walk from the nearest

road, only a few people spoke Lao, and they had nothing modern in the

entire village. There was no clocks, no school, no hospital, no

institutions. They all worked together, played together and took care of

the children together. Perhaps it is these children’s right to receive

an education, but then you would have to construct roads into this

community, and by doing that you would destroy them - the children would

grow up in a completely different culture from what their parents had,

and this would tear the society apart. (Because of incredible corruption

and greed in Laos, this happened - many indigenous communities were

forcefully moved down from the hills to the valleys, because the

government wants to exploit rubber plantations and power plans. They

will probably end up with many of the same problems that indigenous

people face around the world - alcoholism, family violence…)

The

right to refuse?\

Greg

Francom

makes an interesting point about “the right to refuse” for for example

indigenous people. I think this is a very interesting point, and I have

two examples. When I was in Laos, I joined an organized walking tour

into an indigenous community. They lived a day’s walk from the nearest

road, only a few people spoke Lao, and they had nothing modern in the

entire village. There was no clocks, no school, no hospital, no

institutions. They all worked together, played together and took care of

the children together. Perhaps it is these children’s right to receive

an education, but then you would have to construct roads into this

community, and by doing that you would destroy them - the children would

grow up in a completely different culture from what their parents had,

and this would tear the society apart. (Because of incredible corruption

and greed in Laos, this happened - many indigenous communities were

forcefully moved down from the hills to the valleys, because the

government wants to exploit rubber plantations and power plans. They

will probably end up with many of the same problems that indigenous

people face around the world - alcoholism, family violence…)

I also wanted to mention an interesting movie that I watched in Indonesia, called Denias. It was very beautifully filmed, about a boy in an isolated village in Papua (the Indonesian part - also called Irian Jaya) who went to a tiny school taught by a teacher from Jawa who came by helicopter to live in their village. It portrays the teacher and also the resident military officer as heroes, and the father who is reluctant to have his son attend class, and rather wants him to help in the fields as at worst egoistical and at best ignorant and backwards. The school children beg the teacher to provide them with uniforms, and finally they get airlifted in some uniforms donated from Jawa. Then the teacher has to leave, and to pursue further education, Denias leaves his village and family and goes to the big mining town, where he finally manages to beg himself to a space at the fancy school for elite children, taught by fair skinned Jawanese.

AFeministBlog refers to the following conversation, and uses it as an example of how the indigenous don’t realize “what is good for them” *\ \ Maleo: I need your help to make Denias able to study again.\ Samuel: Don’t interfere my affair. That is not your duty.\ Maleo: I know this is not my duty but your duty.\ Samuel: This is not Java. All sons have to help their parents. You don’t understand that.\ Maleo: I understand that. That’s why Denias has to study. If he studies, he will be able to help you a lot later.\ Samuel: That’s it. You only can say later later and later. What I need is now now and now.\ *\ However, in the film’s “postscript” it is revealed that Denias later gained a full scholarship from the mining corporation to go study in Australia, and that he is now living in Australia. So - what benefit has his schooling brought to his parents, to his village?

These were a few comments based on the idea that primary schooling as it is realized today is mainly good - with some important changes (it should be accessible in the local language, teaching a relevant local curriculum, maybe it’s not appropriate for indigenous people etc). However, what if we change tack, and state that schooling is actually negative?

An

alternative to schooling?\

When I was younger, I often discussed education at length with my

friends, and the system we came up with was strikingly similar to Ivan

Illich’s thoughts, which I was only to read many years later in

Deschooling Society (whole text available

online).

He is very sceptical to institutions which tell you how you should learn

and stifles creativity and curiosity in children - instead of a

compulsory number of years of education that is separate from everything

else and conducted by professionals, he proposes a much more flexible

system where pupils learn what they want to, from each others and from

elders in society who want to teach, while at the same time contributing

to society. I always thought that there was nothing intrinsically wrong

with children working - I loved coming to my father’s work when I was

young, and helping him with different things, it taught me much about

society and made me feel valuable. It is forcing children to do

demeaning and dangerous work that is wrong.

An

alternative to schooling?\

When I was younger, I often discussed education at length with my

friends, and the system we came up with was strikingly similar to Ivan

Illich’s thoughts, which I was only to read many years later in

Deschooling Society (whole text available

online).

He is very sceptical to institutions which tell you how you should learn

and stifles creativity and curiosity in children - instead of a

compulsory number of years of education that is separate from everything

else and conducted by professionals, he proposes a much more flexible

system where pupils learn what they want to, from each others and from

elders in society who want to teach, while at the same time contributing

to society. I always thought that there was nothing intrinsically wrong

with children working - I loved coming to my father’s work when I was

young, and helping him with different things, it taught me much about

society and made me feel valuable. It is forcing children to do

demeaning and dangerous work that is wrong.

Andreas Formiconi brought me a link to the Indian organization Shikshantar - The People’s Institute for Rethinking Education and Development, that had quite a few writings very critical to the culture of schooling. Here is an excerpt from their list of critiques of “the Culture of Schooling”:\ *\ 1) Labels, ranks and sorts human beings. It creates a rigid social hierarchy consisting of a small elite class of ‘highly educated’ and a large lower class of ‘failures’ and ‘illiterates’, based on levels of school achievement.\ 5) Confines the motivation for learning to examinations, certificates and jobs. It suppresses all non-school motivations to learn and kills all desire to engage in critical self-evaluation. It centralizes control over the human learning process into the State-Market nexus, taking power away from individuals and communities.\ 7) Fragments and compartmentalizes knowledge, human beings and the natural world. It de-links knowledge from wisdom, practical experiences and specific contexts.\ 9) Privileges literacy (in a few elite languages) over all other forms of human expression and creation. It drives people to distrust their local languages. It prioritizes newspapers, textbooks, television as the only reliable sources of information. These forms of State-Market controlled media cannot be questioned by the general public.\ 10) Reduces the spaces and opportunities for ‘valid’ human learning by demanding that they all be funneled through a centrally-controlled institution. It creates artificial divisions between learning and home, work, play, spirituality.\ 12) Breaks intergenerational bonds of family and community and increases people’s dependency on the Nation-State and Government, on Science and Technology, and on the Market for livelihood and identity.\ \ *In their different documents, Shikshantar echo many earlier writers who have criticized institutional and state-run education.

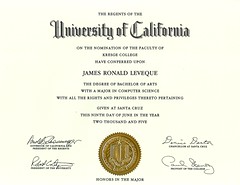

Credentials

are wrong?\

Shikshantar also started a movement to stop using diplomas to assess

people’s

value, and

encourage people and organizations to worry less about credentials and

grades, and use more holistic means of assessment. While this sounds

great, it does remind me of the history of College admissions in the

US

which tells us that enrollment based on pure academic merit led to

enrolment of Jews at Harvard in the 1920’s reaching 20%. Pure

antisemitism then led the College administration to come up with new

ways of keeping Jews out of their school, and they ended up with an

“all-rounded” evaluation, where you would write application essays,

submit references etc. Now they could turn away the students that had

scored the best (and were Jews) because of non-measurable factors. I

cannot help but think that today’s equivalent is the middle class kid

who has spent a gap-year in India, and worked for a whole summer as an

unpaid intern with the UN in New York, versus the working class kid who

has worked equally hard and gotten equally good grades, but couldn’t

afford to do an unpaid internship, and had to work at McDonald’s

instead. Who do you think will get the job?

Credentials

are wrong?\

Shikshantar also started a movement to stop using diplomas to assess

people’s

value, and

encourage people and organizations to worry less about credentials and

grades, and use more holistic means of assessment. While this sounds

great, it does remind me of the history of College admissions in the

US

which tells us that enrollment based on pure academic merit led to

enrolment of Jews at Harvard in the 1920’s reaching 20%. Pure

antisemitism then led the College administration to come up with new

ways of keeping Jews out of their school, and they ended up with an

“all-rounded” evaluation, where you would write application essays,

submit references etc. Now they could turn away the students that had

scored the best (and were Jews) because of non-measurable factors. I

cannot help but think that today’s equivalent is the middle class kid

who has spent a gap-year in India, and worked for a whole summer as an

unpaid intern with the UN in New York, versus the working class kid who

has worked equally hard and gotten equally good grades, but couldn’t

afford to do an unpaid internship, and had to work at McDonald’s

instead. Who do you think will get the job?

These are important readings, because it is so easy to take schooling for an unequivalent good thing. Indeed, I remember reading an article saying that when literacy activists went into an area to teach literacy, they produced illiterates. Before, there were no illiterates, only people. With skills, stories, social roles. Then suddenly, they were “made” illiterate by these external forces, which defined them as lacking. This is not to say that literacy (in your mother tongue) cannot be a huge bonus, but we need to be far more sensitive to the possible negative consequences of schooling. I believe that some readings that highlighted these ideas should be included in the reading list to balance off the overly positive view of schooling expoused by Tomasevski.

Conclusion?\ I have muddied the waters enough, and I need to answer the questions. The first one is easy, yes I do believe that the right to education is a human right - it is what enables to to realize what it is to be human, and it is what enables us to realize many other human rights, like political participation. However I do not think that education and schools are synonymous. I do believe that ideally a child can receive a perfectly good education outside of the standard school system - learning from her elders, from her peers, exploring the world around her and creating meaning. That is an idealized picture, and it might be that a number of years of decent quality institutional elementary school is all we can hope for in some countries. But we should never leave that uncontested as the final ideal.

Stian\ (Diploma photo (cc) blue_j @ flickr.com)

Stian Håklev August 31, 2007 Toronto, Canada comments powered by Disqus